Chapter 7 of the Outline of basic music theory – by Oscar van Dillen ©2011-2020

Chapter 7 of the Outline of basic music theory – by Oscar van Dillen ©2011-2020

The beginner’s learning book can be found at Basic elements of music theory.

Overview of chapters:

Chapter 1: Introduction

Chapter 2: Sound and hearing

Chapter 3: Musical notation

Chapter 4: Basic building blocks of melody and harmony

Chapter 5: Consonance and dissonance

Chapter 6: Circle of fifths and transposition

Chapter 7: Concerning rhythm, melody, harmony and form

Chapter 8: Further study

Rhythm

Definition of rhythm

Rhythm is the timed sequence of sounds in music.

Time, beat, subdivision and feel

Most rhythm has a regular beat, which can group a finer division into larger units for practical counting, and which is also used for dancing. A cycle of beats is called the time. Within cycles of beats, there are usually stronger and weaker beats (sometimes also called arsis and thesis). The subdivision of each beat can be called the ”feel”.

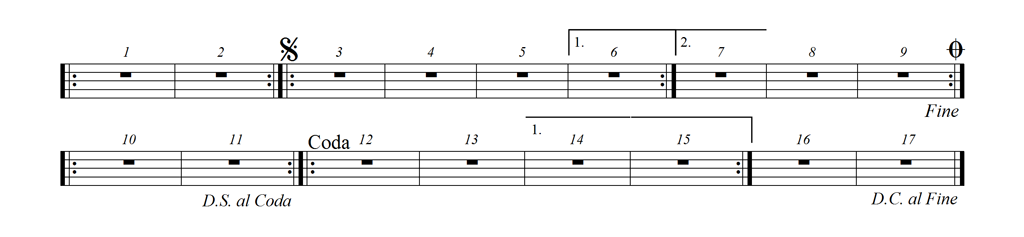

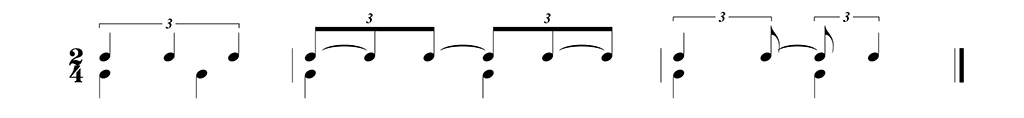

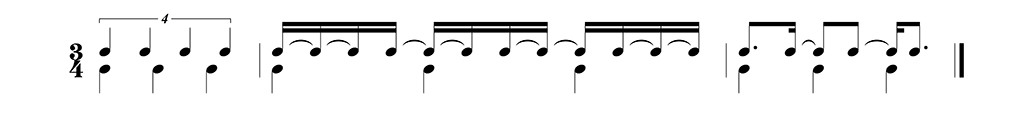

Basic subdivisions of the beat

We will now look at the possible subdivisions per beat, in basic notation. In the examples below, you will therefore find a list of all possible subdivisions of both the quarter and the dotted quarter note, for binary and ternary time signatures.

Even though there are a great many possibilities already within these limits, I further limited the examples to a maximum resolution of 1/16 note, meaning that no smaller notes are involved, notated and listed. These rhythms do reach a certain degree of complexity, and even more complicated rhythms usually involve tuplets.

Still, the “catalogue” below lists commonly encoutered rhythmic building blocks, and studying -and being able to quickly recognize, clap or tap- these examples, greatly enhances one’s ability to connect and integrate one’s hearing-reading-singing (clapping)-writing as was explained in the introduction of this outline.

Binary subdivisions

The basic subdivisions of the quarter note for binary time signatures, up to a resolution of 1/16 notes, is found on the image below.

binary subdivisions of the quarter note

The building blocks exercises with these binary subdivisions are found here:

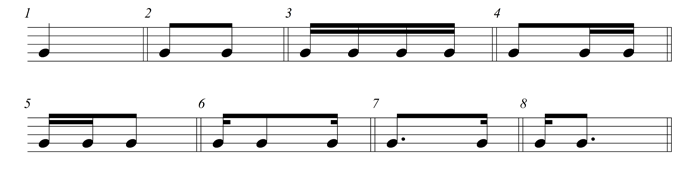

Ternary subdivisions

The basic subdivisions of the dotted quarter note for ternary time signatures, up to a resolution of 1/16 notes, is found on the image below.

ternary subdivisions of the dotted quarter note

The building blocks exercises with these ternary subdivisions are found here:

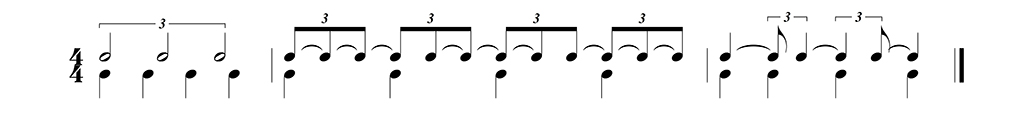

Polyrhythm

Polyrhythm is the simultaneous presence of more than one beat or feel in the same music.

The patterns below present the basic polyrhythmic patterns based on 2, 3 and 4 in mutual combinations. These should be practiced one after the other with two hands, while always keeping the beat in the same hand. The beat patterns here are notated with notestems downwards.

In the examples every first bar offers a tuplet notation, every second bar offers a notated analysis with the smallest common beat-particles regrouped by tying together, every third bar offers a practical notation which is best for performance (and especially much clearer than duplets and quadruplets).

3 against 2

2 against 3

4 against 3

3 against 4

Some more advanced exercises with triplets are found here:

Melody

Definition of melody

Melody is created by a sequence of different single pitches in time.

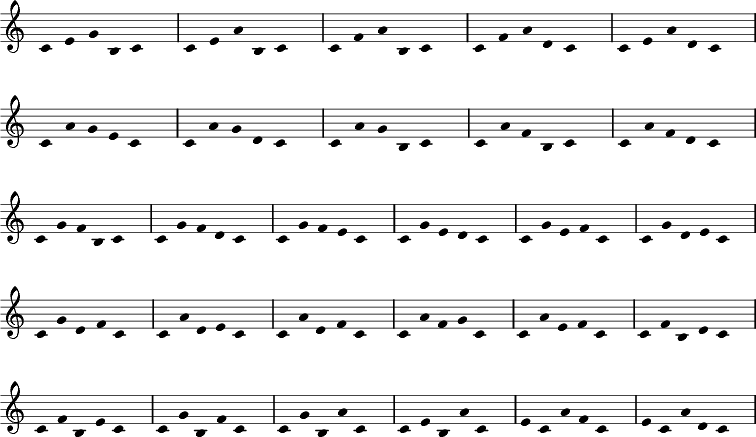

Exercise in melodic building blocks

The following exercise makes use of the hexachord and a leading tone, 6 above and 1 below c.

To be sung without accompaniment, all in this order, without halting, in major:

All these melodies above should also be practiced in the church modes; below they are given in harmonic minor:

All these melodies above should also be practiced in the church modes; below they are given in harmonic minor:

Printable versions of melodic building blocks

The following complete and printable versions of the melodic building block solfeges in pdf can be found here:

- Melodic building blocks – only in C, one page (pdf)

- Melodic building blocks – in all keys (G clef), booklet (pdf)

- Melodic building blocks – in all keys (F clef), booklet (pdf)

- Melodic building blocks – Lower hexachord, only in C, one page (pdf)

- Melodic building blocks – Lower hexachord, in all keys (G clef), booklet (pdf)

- Melodic building blocks – Lower hexachord, in all keys (F clef), booklet (pdf)

Harmony

Definition of harmony

Harmony is created by the interrelationships of different pitches together in time; the timing of the sounds used, called harmonic rhythm, is an ingredient as essential as the sounds themselves!

Functional harmony

Whereas harmony in general is a concept which describes the relative sounds of large groups of tones, the term functional harmony is used for a specific, yet generally used, type of harmony, generating the expectation of a central tone or chord, called the tonic, by means of tension and resolution.1

Functional harmony rests on three pillars, called functions:

- Tonic: a “home” sound or chord, a resting place within the progression of chords

- Dominant: a point of maximum tension relative to home, the “going home” chord, creating expectations of resolution

- Subdominant: an alternative resting place, though not “home”, but rather perhaps an “out, on a holiday” chord, anything can happen after this

Functional harmony can create story-like structures in time with these elements, relatively easy to hear and follow, even for non-trained ears.

Not all harmony is functional! Harmony can also be non-functional, in which case the expectation of a tonic is absent, even though an harmonic focus can be present. Among non-functional harmony there exist such phenomena as modal harmony, parallel harmony, and atonality.

Definition of degree

A degree is a harmonization of a particular scale-step, indicated by a Roman numeral.

A degree exists in relation to an audible functional harmonic center, called the Tonic, symbolized by a I. Relative to this I, other degrees are numbered around it. If another degree than the I forms a temporary harmonic center, this is created by at least one Secondary degree, usually a Dominant sometimes accompanied by a Subdominant degree.

Degree as chord

Any scale can be harmonized by forming triads, seventh- or other chords on its steps. The harmony thus obtained is proper to that particular scale itself and can be modal or tonal, depending on its use.

Mostly, degrees are formed by a construction of thirds, but this can also be done with other intervals.

Degree as scale

New scales or modes can be derived from any particular scale, by using the scale on a degree of another scale. Thus the church modes, the harmonic minor modes and the melodic minor modes can be found, but one could also imagine this method as a starting point for harmonizing very different modes still, such as a Carnatic raga or a Turkish makam.

Basic degrees as triads

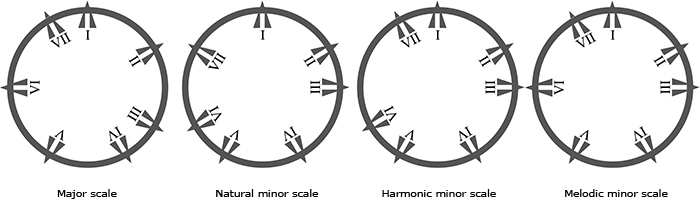

Degrees can be shown as part of a circle of degrees:

Circles of degrees as built on the four basic major and minor scales

This modal approach does not always correspond to the functional tonal use of degrees, but does enlarge the number of possibilities. In such a way, modal elements can be added to tonal music.

We shall proceed however with the most basic triads, occurring not on the scales, but rather in the keys of, major and minor.

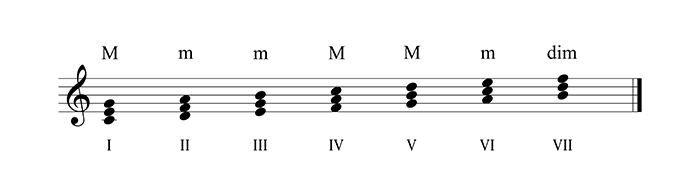

Basic degrees in major

The basic major scale (in c consisting of basic tones) generates the degrees given below.

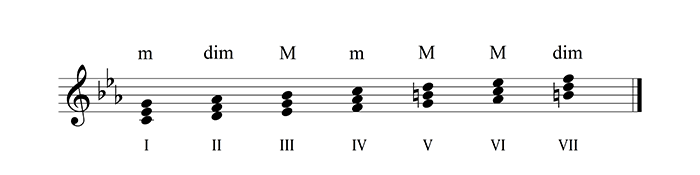

Basic degrees in minor

The basic degrees used in minor are given below (example in c minor) :

Basic degrees as seventh chords

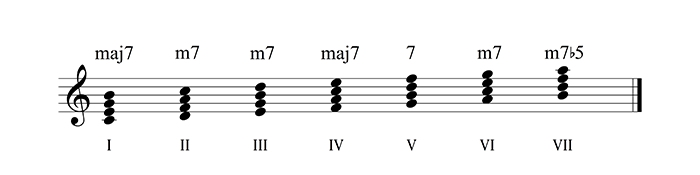

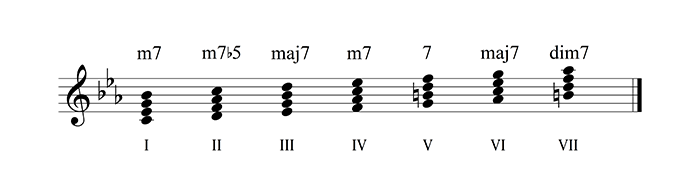

Seventh chord degrees in major

The major scale generates as seventh chords the degrees given below:

Seventh chord degrees in minor

The basic degrees as seventh chords, as used in minor are given below:

As can be seen in these degrees, the use of the leading tone b here is restricted to the dominant degrees V and VII, but it does also occur as fifth in III and seventh in I. These more complicated chords are used more rarely but they do occur. The same can be observed with the 6th step of the scale, which was already encountered in the relative wealth of options offered by the minor scales, especially in the upper tetrachord 5-(b)6-(b)7-8.

The student should investigate the possible degrees and chords resulting from these different options. They are many, as both of these tones can serve as 1, 3, 5 or 7 of a chord.

More advanced use of degrees

In all keys, but especially in minor, there is a more colorful use of degrees than described in the basic examples above. Such advanced use can be seen to sound like borrowing and incorporating the sound of church modes into the key, such as the use of a Phrygian flat 2nd, the b2 as part of a temporarily underlying scale. Also the Lydian sharp 4, the #4 is commonly incorporated. Both of these tones have a secondary leading tone quality, as they harmonically point ahead to a resolution (b2 > 1 and #4 > 5).

If a dominant degree V is employed as resolving into another degree than a tonic, for example resolving to a clear II, we speak of a secondary dominant, symbolized by (V). Also a secondary leading tone chord (VII) is often encountered. These may or may not be accompanied by respective belonging subdominants, such as occurs in the example of (II V) > VI in which the II of VI is also out of the key. Secondary degrees are like “borrowed” from the key of the chord they are resolving into, including it being major or minor.

Molldur and Durmoll

In more advanced use of functional harmony, the colors of major and minor are mixed, these phenomena are called molldur and durmoll, after the German use of the terms. Dur (originating from Latin: hard) means Major, and moll (also originating from Latin: soft) means minor.

- Molldur is the use of degrees borrowed from minor, into a major main context

- Durmoll is the use of degrees borrowed from major, into a minor main context

In general, the alteration of the 3rd and/or 6th note of the key leads to this phenomenon.

Although no general statistics can be given, and all occur in all styles and genres, Molldur is slightly more common in Classical and Jazz, whereas Pop music tends to use Durmoll more often.

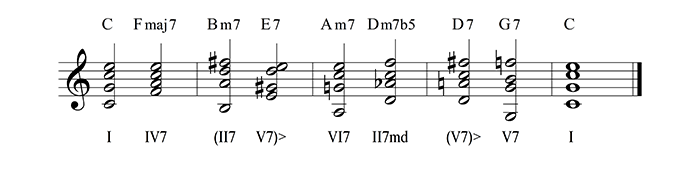

The examples below give a progression in major, making use of all these more advanced elements:

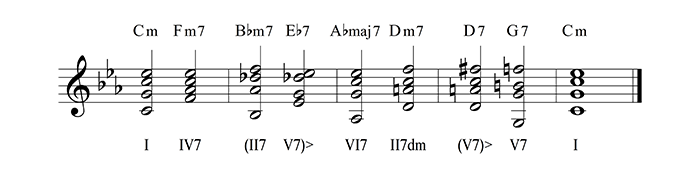

And finally here is a corresponding one set in minor:

The analysis of each chord is given below (the degree symbol is traditionally placed below a chord), whereas the chord symbols are always written above the chords.

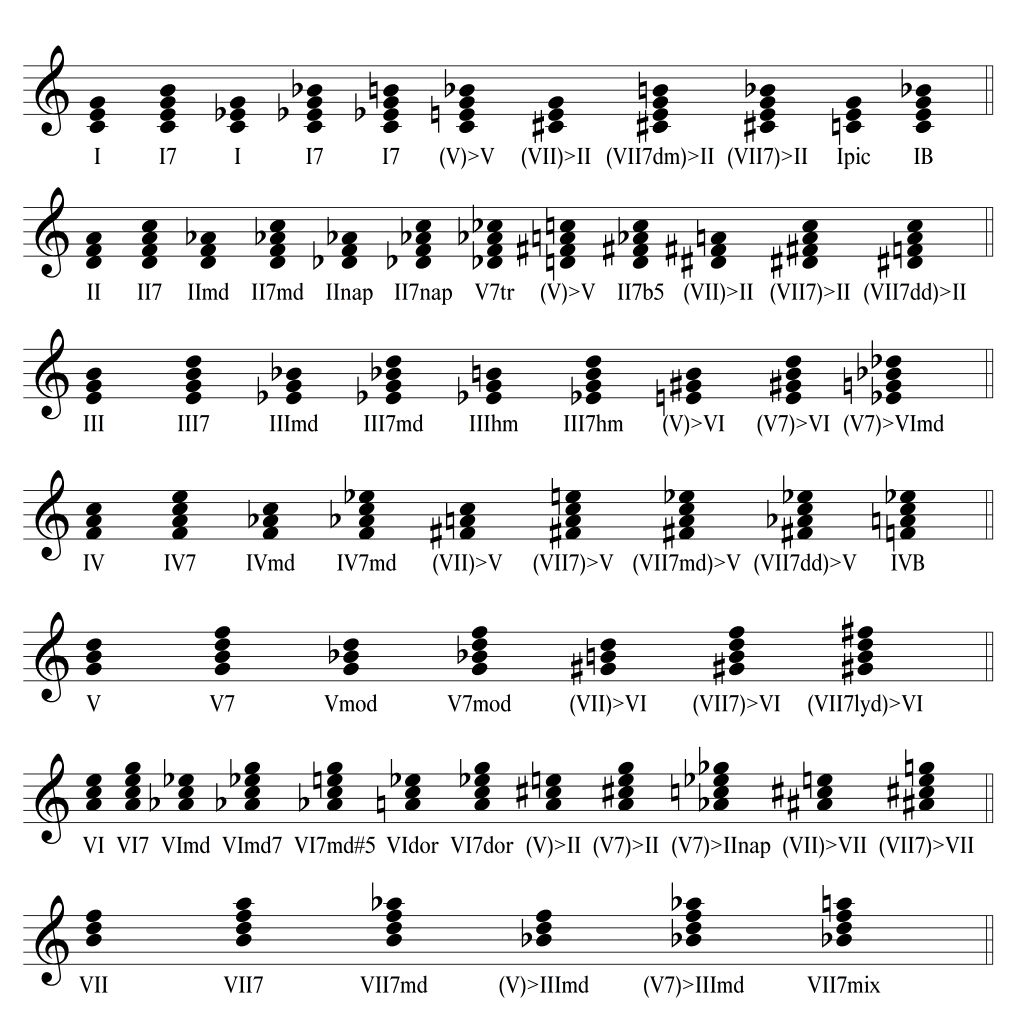

Tentative catalogue of concentric degrees

For easier reference, below a tentative catalogue of all possible concentric degrees is given. This overview – in the key of C major – should not be used as a general table for harmonic analysis, as degrees are relative functions of chords, and should always be evaluated in their context. Nevertheless, this overview may serve a purpose of preparing the student for many things which do in fact occur, concentrically, which means: without leaving the key (here: of C major). The very same chords should, when leaving the key, of course be analyzed differently, in relation to the key into which the modulation (change of key) takes place.

tentative catalogue of all possible concentric degrees

Abbreviations used:

- pic – picardian, meaning a major tonic at the end of a minor cadence

- 7 – added to any degree which is not a triad but a seventh chord

- md – molldur, meaning a degree borrowed from the equal minor (here: from C minor)

- dm – durmoll – meaning a degree borrowed from the equal major (here: from V major)

- (V )> – secondary dominant pointing at resolution

- (VII)> – secondary leading tone chord pointing at resolution

- tr – tritone related dominant (resolving a minor second down)

- B – blues degree (only possible on I, IV and occasionally VII)

- nap – napolitan chord, derived from the phrygian mode

- b5 – major flat 5 dominant seventh chord

- dd – double diminished alteration of the degree

- hm – harmonic minor, degree derived from the harmonic minor scale

- mod – modal degree, specifically used for V with a minor third

- dor – dorian degree, derived from the dorian mode

- mix – mixolydian degree, derived from the mixolydian mode

The degree symbols used here are by no means standardized internationally. There are many systems and nomenclatures in use today, often used solely in certain national schools of music theory.

For a progression which in the system above would be rendered as: II V VI III IV Ipic

other systems would use minuscule Roman numerals such as: ii° V VI III iv I

and still other systems prefer using the alphabet such as sp D tP tG s T

Exercise

An advanced exercise in singing or determining degrees with c as a tonal centre in major and minor can be found here:

Form

The concept of form in general depends on the human awareness being capable of distinguishing an object from its surroudings. An awareness without this ability to distinguish would be able to experience a totality of being, or stream of awareness, yet without objects, so it would not be aware of its own being itself at the same time, a state of mind often mistaken for nirvana, which does not use the full capacity of human understanding. To be aware of oneself and one’s surroundings at the same time, creates the awareness of identity and differences, the awareness of objects, or forms, themselves being identities, as such like yet apart from oneself, all separated from their surroundings by the boundaries perceived in time and space.

When thinking of “Form in art” one usually thinks of the visual arts, where forms are distinct objects in space. In music though, “Form in music”, “objects” are not primarily perceived in space, but in time. Both abilities, to distinguish between forms in space, and forms in time, develop at least from birth onwards, as a child learns quickly to not only distinguish the faces of its parents from other surrounding phenomena, but also their voices from other surrounding sounds. Both abilities depend on the function of ”memory”, yet the dependence on memory is stronger with sound, because sounds disappear in time and comparison has to always be done in memory2. Without memory, no awareness of form in music is possible: music is primarily (though not exclusively) a ”time-art”.

These philisophical considerations being mentioned, for this outline it is sufficient to mention that there are many forms in many music styles, and even concepts which transcend the concept of form, though not being something totally different. Below an incomplete list of examples is given of well-described forms, which are part of music theory:

- Antiphon – vocal form with a cantor or small group singing verses while the whole choir or congregation respond with a refrain

- Conductus – a type of sacred, but non-liturgical vocal composition for one or more voices, usually rhythmic, as befitting music accompanying a procession, and almost always note-against-note

- Ballatá – a musical form in use from the late 13th to the 15th century, with a structure AbbaA, and the first and last stanzas having the same texts

- Virelai – a song form of the 14th and early 15th century usually has three stanzas, and a refrain that is stated before the first stanza and again after each ABBA

- Rondeau – a late 13th and the 15th centuries form, which is structured around a fixed pattern of repetition of material involving a refrain, with shorter, medium and very long realizations such as AB-aAab-AB or ABBA–ab–AB–abba–ABBA or even AABBA–aab–AAB–aabba–AABBA

- Madrigal – (1) late 13th century Italy: a composition for two (or rarely three) voices, sometimes on a pastoral subject (2) 16th century Italy: a through-composed strophic 4-6 part secular vocal form

- Fugue – a contrapuntal instrumental form with usually three sections: an exposition, a development, and a recapitulation containing the return of the subject in the fugue’s tonic key (though not all fugues have a recapitulation)

- Minuet – an instrumental form which accompanied a dance in 3/4, often with a longer structure called minuet and trio

- Allemande – one of the most popular instrumental dance forms in Baroque music, in 2/4 or 4/4

- Gigue – a Baroque dance, derived from the English jig, usually in 3/8 or in one of its compound metre derivatives, such as 6/8, 6/4, 9/8 or 12/8, although there are some gigues written in other metres, as for example the gigue from Johann Sebastian Bach’s first French Suite (BWV 812), which is written in 2/2

- Sarabande – a slow dance in triple metre

- Suite form – an ordered set of instrumental or orchestral/concert band pieces, usually connected by key

- Sonata form – this form consists of three main sections: an exposition, a development, and a recapitulation, with specific relationships of themes and their keys

- Rondo – a form where a principal theme (sometimes called the “refrain”) alternates with one or more contrasting themes, generally called “episodes”, such as ABA, ABACA, or ABACABA

- Ländler – a folk dance in 3/4 time which was popular in Austrian-Hungarian Empire at the end of the 18th century

- Waltz – a popular dance from the 19th century in 3/4, where movement was continually rotating instead of more forward as in the mazurka

- Song form – also called ternary form is a three-part musical form, usually schematized as ABA

- Blues – a cyclic musical form in which a repeating progression of chords mirrors the call and response scheme commonly found in African and African-American music, the most basic blues form has 12 bars with the harmony I IV I I – IV IV I I – V VI I I

- Ballad – originally literally a “dancing song”, in jazz: a slow song form

- Mambo – a musical form and dance style invented in 1938 by the brothers Orestes and Cachao López, within a danzón, a dance form descended from European social dances like the English country dance, French contredanse, and Spanish contradanza, it was backed by rhythms derived from African folk music; the word “mambo” means “conversation with the gods” in Kikongo, a language spoken by Central African slaves taken to Cuba

- Montuno – the final section of a song-based composition, usually a faster semi-improvised instrumental section, sometimes with a repetitive vocal refrain

- Descarga – literally: “discharge”; freely improvised form in Cuban music

- Raga – a tonal framework for composition and improvisation in Indian classical music

- Alap – a form of non-rhythmical melodic improvisation that introduces and develops a raga in Indian classical music

- Jor – a form of melodic improvisation that introduces and develops a raga with a simple pulse but no well-defined rhythmic cycle in Indian classical music

- Jhala – a form of melodic improvisation that introduces and develops a raga with a fast pulse but no well-defined rhythmic cycle in Indian classical music

- Sargam – a two part song form in Indian classical music, the first part being called Asthai and the second Antara

- Gat – a fixed, melodic composition in North Indian vocal or instrumental music, set in a specific raga, performed with rhythmic accompaniment by a tabla or pakhavaj

- Makam – a complex set of rules for composing and performance in Turkish classical music

- Taksim – a melodic musical improvisation that usually precedes the performance of a traditional Arabic, Greek, Middle Eastern, or Turkish musical composition

This list of examples is far from complete of course, and intended to give a first impression of the wealth of musical forms that exist; it even contains different concepts of what can be considered musical forms, all in one list. Any fuller description of even just these, including the attempt of giving a more complete list of forms, would certainly have to become a book in itself.

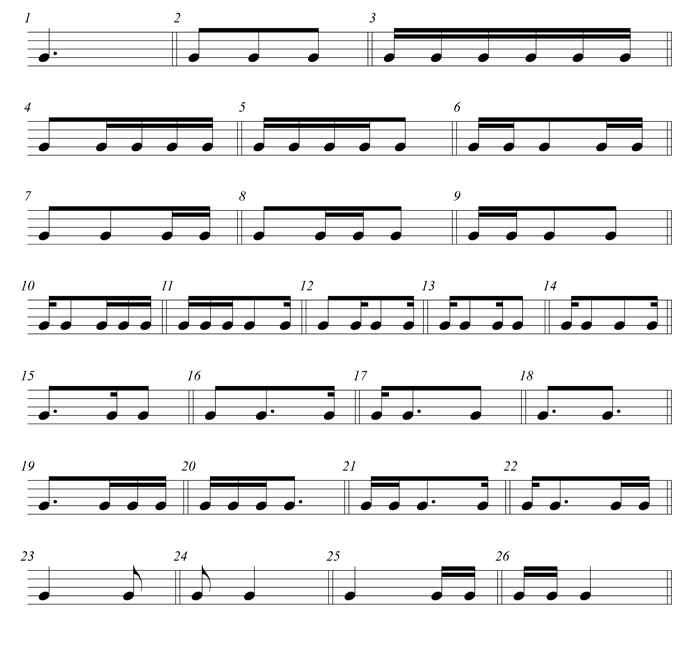

Traditional Italian score indications concerning form

The following musical form indications are customarily written in Italian:

| Da Capo (D.C.) | from the beginning: back to the top |

| Dal Segno (D.S.) | to the sign (slashed S with dots) |

| Coda | final part of the form (circle with crosshairs) |

In the following complex imaginary example all these are used to create a longer form in relatively short notation, as all bars are played several times:

The order for performance is rather complex and should run as follows:

1-2 (repeat) 1-2 (sign is for later return) 3-4-5-6 (repeat under 1) 3-4-5-7 (continue under 2) 8-9 (here we have three signs, and an interpretation is needed to decide which one is intended here and still leads to a complete piece, here: the repetition sign goes first, to the closest forward repetition sign) 3-4-5-6 (repeat) 3-4-5-7-8-9 (second time here we would fully skip bars 10 and 11 if we follow the cross-haired sign, so we first just continue – actually here it would help if a 1st/2nd would be indicated of course, but this, as most examples here, are of theoretical nature, and indeed printed scores are not known to be always crystal clear with such signs…) 10-11 (first repeat) 10-11 (now interpret Dal Segno al Coda: go to the Segno sign) 3-4-5-6 (repeat) 3-4-5-7-8-9 (repeat) 3-4-5-6 (repeat) 3-4-5-7-8-9 (third time here we follow the cross-haired sign, which means go to the Coda, which corresponds to the earlier encountered D.S. al Coda sign) 12-13-14-15 (under first repeat) 12-13-16-17 (as second, skip the two bars under first repeat, and now Da Capo al Fine) 1-2 (repeat) 1-2-3-4-5-6 (repeat from 3) 3-4-5-7-8-9 (repeat from 3? probably just end here)

More score indications concerning form have been presented at the section score indications concerning form in the chapter Musical notation.

Oscar van Dillen ©2011-2020

goto chapter 8 ► Further study

Footnotes

- see also the last chapter of the Basic elements of music theory ↩

- “When you hear music, after it’s over, it’s gone, in the air. You can never capture it again.” (Eric Dolphy) ↩