Introduction

Music theory, or theory of music, is the practical science which studies the structural functioning of music. It is mostly studied by musicians.

Practical science

Music theory is a science, because it researches, classifies and evaluates musical phenomena, structures and elements, creating models for explanation and prediction. Yet music theory is also a practical science, since many evaluations can only be done by experiments in careful hearing, listening and performing.

History of music theory

Theory of music is not an exclusively Western science, as many other traditions of world music have developed and maintained their own theories. A unique history of theory of music can be developed for many continents, going back millennia. Yet, as music recording is hardly over a century old, a largely unwritten history also exists and is difficult to trace, because it is based on the many oral traditions that abound in music, also in literate parts of the world.

Basic elements of music theory

For the aspiring but musical theoretically beginning musician, the online learning book Basic elements of music theory offers a beginner’s excerpt from the materials presented in the more advanced Outline (see below), preparing the student for the entrance requirements of a professional music education. The Basic elements also offers many tips and exercises.

Outline of basic music theory

To help students acquire a basic working knowledge of music theory, this website presents the Outline of basic music theory, which offers a logical order of study. This online professional learning book, and its companion, the current reference page on music theory, represent a complete professional course in basic music theory for students in many fields, styles and traditions.

Music theory (reference guide)

The current page Music theory shows a complementary alphabetical overview of concepts, in alphabetical order, for purposes of reference.

Partial fields of study

Theory of music can be divided into many partial fields of study, including:

- Notation

- Harmony

- Melody

- Rhythm

- Counterpoint

- Instrumentation

- Form

- Style

Related fields of study

Theory of music can be part of related fields of study, such as:

- Musicology

- Ethnomusicology

Alternative theoretical models

Some composers developed their own systems of musical theoretical thought. Especially when these were more like procedures for creating music (instead of for general analysis), these were often not incorporated into the generally taught theory of music. Some alternative musical theoretical models however have entered main stream music theory education.

Below are some alternative and additional musical theoretical models and systems:

- Schenkerian analysis

- Dodecaphony

- Serialism

- Set theory

- Tone clock

- Lydian chromatic concept of tonal organization

About this page

On this page you find an overview of definitions of the most relevant concepts in music theory, organized alphabetically, as in a dictionary, but additional information can also be found, as in a musical theoretical encyclopedia.

I suggest therefore this page to be at all times studied together with the outline of basic music theory and/or the basic elements of music theory on this website.

Finally, the page vocabulary for music theory may be of help for the serious student.

© Oscar van Dillen 2012

Alphabetical reference on music theory

Alphabetical reference on music theory

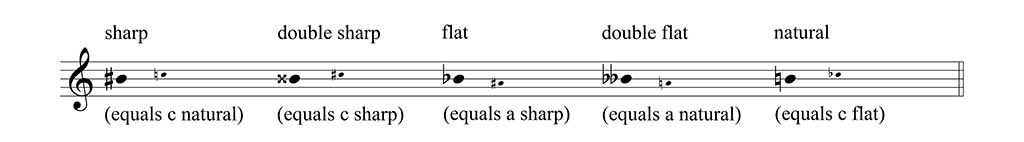

Alteration

Alteration in music is the changing of a basic tone, by raising or lowering it’s pitch with one or two semitones or other microtones, thus enhancing the diatonic to a chromatic system.

In notation the following signs are used for this:

- Sharp, to raise the pitch by one semitone

- Flat, to lower the pitch by one semitone

- Double sharp, to raise the pitch by two semitones

- Double flat, to lower the pitch by two semitones

- Natural, to correct any of the previous alterations

Bar

A bar or measure is a unit of time in notation. Two adjacent bars are separated by a barline, the length of a bar is determined by the time signature.

Bars can be numbered; to indicate a particular passage in a composition, it is customary to mention the bar number(s).

Barline

A barline is a symbol in notation to separate bars. This symbol is usually a simple vertical line on the staff or staff-system.

Other types of barlines include:

- Barlines between staves in a staff-system (to avoid visually impairing the flow of music, especially suited for transciptions of polyphonic mensurally notated music)

- Ticks, small lines on top of a staff, usually running at a certain metronome speed, an invention of Luciano Berio in his Sequenza I for solo flute (1958).

Basic tone

Definition

There are 7 or 5 basic tones in most music, from which all other tones are derived by alteration.

Basic tones are the basic building blocks of any scale, whether this is a (diatonic) scale, a church mode, a thaat, a makam or other. Basic tones occur in different nomenclatures.

Note that a tone denotes a pitch, and not a note.

Systems for basic tones

Internationally there are various and different systems and nomenclatures for basically the same or similar basic tones, some of which are used exclusively for particular styles. A brief overview is given here, but the student should be aware that every system below has its own (often classical) musical and traditional context, and particularities of application, as well as its own theoretical background, so one cannot always rely on simply translating one complex system into another:

- a, b, c, d, e, f, g – Basic alphabetic nomenclature used in general music theory here

Other systems include, in alphabetical order:

- ding, dong, deng, dung, dang – Balinese nomenclature (five, with various tuning options)

- keng, shang, chueh, chih and yue – Chinese basic tones (five)

- a, b, c, d, e, f, g, h – German alphabetic nomenclature (eight)

- sa, re (ri), ga, ma, pa, dha, ni – Indian nomenclature (seven)

- kyû, syô, kaku, (ritu-kaku,) ti, u (and: hen kyû) – Japanese nomenclature (five, seven, and twelve)

- laras, miring, (bungur,) sanga, sepuluh, panjang (or: blong, barang) – Javanese nomenclature

- hap, sa, il, sang, ku, ch’ôk, kong, pôm, yuk, o – Korean nomenclature (ten)

- do (ut), re, me, fa, sol (so), la, si (ti) – Latin nomenclature

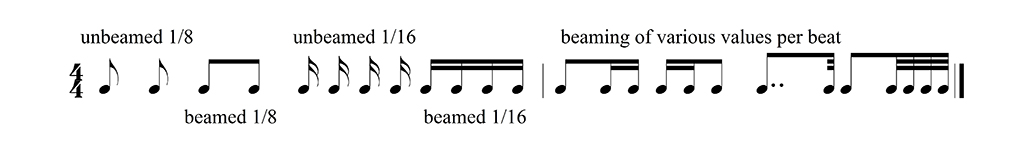

Beam

A beam in notation is a bold horizontal line connecting notestems, replacing value-flags attached to the latter.

Beat

A beat is the practical counting-unit in music. The number of beats per minute (bpm) determines the metronome speed, and indicates the tempo of the music.

bpm

bpm means beats per minute, and is a precise indication of the tempo of the music.

Capital

Definition

A capital is an upper case letter, and the opposite of a minuscule.

In music, a capital can be used to represent a single tone, a chord or a key.

Example of alphabets in capitals

- ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ

- ΑΒΓΔΕΖΗΘΙΚΛΜΝΞΟΠΡΣΤΥΦΧΨΩ

- АБВГДЕЖЗИЙКЛМНОПРСТУФХЦЧШЩЪЫЬЭЮЯ

Chord

Definition

A chord is a special construction of three or more tones sounding together.

Frequently used basic types of chords are triads and seventh chords.

Types of harmonic content in chords

When listening to 2 tones sounding together, their sound quality as interval will stand out more than the tone content (the actual tones played); the tones played can be described to be more or less contained within the sound of the interval. When 3 tones sound together, there will also be 3 intervals sounding together, and it is this intervallic harmonic content which determines the overall sound of any chord, much more than its actual tone content.

When 4 tones sound together, there will be 6 intervals sounding together, and, in the case of seventh chords, also 2 triads sounding together, creating a clearly perceptible triadic content as well.

When listening to chords therefore, the human ear will percieve the following harmonic content:

- intervallic content

- triadic content

- tone content

Detailed musical perception will generally be more or less in this order, but this may vary, and cannot always be predicted merely from notation.

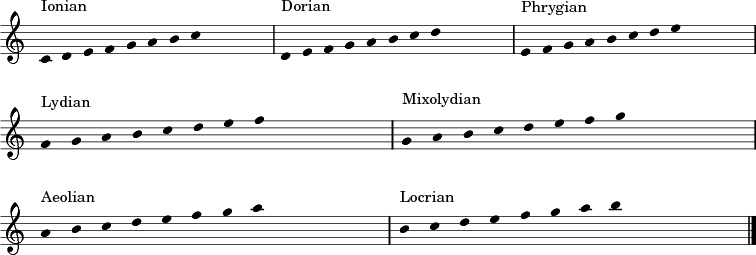

Church mode

A church mode is a mode that is found on a degree of the major scale.

Origin of church modes

“Church modes” is the conventional Western name for the seven basic theoretical diatonic scales and their related derivatives, which have been used in Europe since medieval times. They form the basis of the later major-minor system; their names are derived from Ancient Greek music theory.

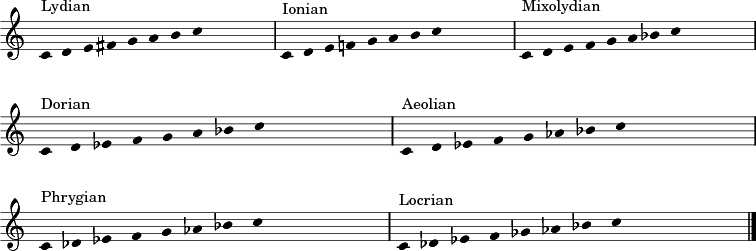

Notation of basic church modes

In their most basic form the church modes can be notated with only basic tones.

Two ways of ordering church modes

One can order the church modes by their order of appearance on degrees of a major scale, I call this the first order:

- Ionian – from c to c

- Dorian – from d to d

- Phrygian – from e to e

- Lydian – from f to f

- Mixolydian – from g to g

- Aeolian – from a to a

- Locrian – from b to b

After transposing these modes to run from c–c, one can order the church modes by their number of sharps and flats, in other words, by their sound, by their their relative consonance or dissonance. In this way, they can be seen as ordered by a diatonic circle of fifths, and there are three groups. I call this the second order:

- 3 major modes

- Lydian, 1-2-3-#4-5-6-7, with 1 sharp, this scale is a major #4 scale

- Ionian, 1-2-3-4-5-6-7, without alterations, this scale is the major scale

- Mixolydian, 1-2-3-4-5-6-♭7, with 1 flat, this scale is a dominant, or major ♭7 scale

- 3 minor modes

- Dorian, 1-2-♭3-4-5-6-♭7, with 2 flats, this scale is a minor natural 6 scale

- Aeolian, 1-2-♭3-4-5-♭6-♭7, with 3 flats, this scale is the natural minor scale

- Phrygian, 1-♭2-♭3-4-5-♭6-♭7, with 1 sharp, this scale is a minor ♭2 scale

- 1 diminished mode

- Locrian, 1-♭2-♭3-4-♭5-♭6-♭7, with 5 flats (as there are more diminished scales, I am actually tempted to propose to call this also the natural diminished scale)

Note that when an additional alterations are added, a second sharp or a sixth flat, the fundamental (1) of the mode is affected. The result is that Lydian and Locrian “morph” into one another by change of fundamental. Charting this phenomenon yields a diatonic circle of fifths. The listing above is however linear, and based on one and the same fundamental, so the resulting #1 Locrian and ♭1 Lydian are not included in it.

spiraling diatonic circle of church modes

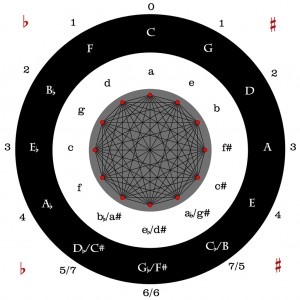

Circle of fifths

The circle of fifths is a circular diagram of all chromatic tones, ordered by perfect fifths.

The circle of fifths is a circular diagram of all chromatic tones, ordered by perfect fifths.

The circle of fifths is a tool to facilitate understanding of the realtionships between, and calculating the exact composition of, intervals, chords, scales and especially keys.

For a complete explanation of the circle of fifths, I refer to the outline of basic music theory (section 4.6).

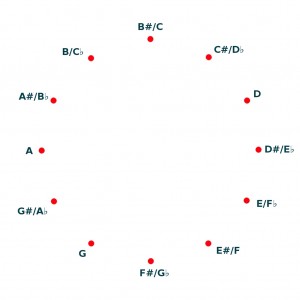

Circle of seconds

The circle of seconds is a circular diagram of all chromatic tones by semitones.

The circle of seconds is a circular diagram of all chromatic tones by semitones.

Clef

A clef (originally from French, meaning: key) determines which pitches are notated on a staff.

In the image above possible clef positions are listed, and middle c is notated where possible.

In the image above possible clef positions are listed, and middle c is notated where possible.

- G-clef as it is used in notation today. It is used for most woodwind instruments, the violin and the for the middle-high register in general. Middle c is notated on one ledger line below the staff. This clef is also employed for some transposing instruments, in which case the notated middle c will actually sound as the instrument’s own fundamental tone, and this relative c can be B♭, E♭, D, E, F, G or A.

- Modern tenor-clef, the 8 denoting transposition an octave down: the notation is an octave higher than the actual sound.

- Rarely used clef for piccolo: the notation is an octave lower than the actual sound.

- Historical clef, no longer in use.

- F-clef as it is used today. It is used for low instruments, such as cello, double bass, bassoon and trombone, and for the low register in general. Middle c is notated on one ledger line above the staff. When employed for double bass it transposes one octave, even though clef nr. 6 would technically be the proper one in this case.

- Transposing F-clef, sometimes used for double bass or bass tuba, see also clef nr. 5.

- Rarely used clef.

- Historical clef for notating instrumental baritone parts, no longer in use. See also clef nr. 13.

- Soprano clef, a c-clef occurring on the first line; historically used for vocal parts.

- Mezzo-soprano clef, a c-clef occurring on the second line; historically used for vocal parts.

- Alto clef, a c-clef occurring on the third line; historically used for vocal parts, but still in use today for viola and the rare alto-trombone.

- Tenor clef, a c-clef occurring on the fourth line; historically used for vocal parts, but still in use today for cello, double bass, trombone and bassoon.

- Baritone clef, a c-clef occurring on the fifth line; historically used for vocal parts. See also clef nr. 8.

- Percussion clef; the position of the noteheads is used to denote specific instruments.

- Another percussion clef; the position of the noteheads is used to denote specific instruments.

Curwen/Kodály handsigns

The Curwen/Kodály handsigns stem from the 19th century and are generally used for visual solmisation to children and deaf people. They can still be a very useful tool for developing melodic imagination and memory in professionals.

The images above show the diatonic scale as do re mi fa sol la si do in Curwen/Kodály handsigns.

Degree

A degree is a functional harmonization of a particular scale-step, indicated by a Roman numeral.

In functional harmonic analysis, a degree is assigned to every chord, according to the perceived function. In a strict sense, there are no true degrees in non-functional harmony.

As there are three harmonic functions, there are three groups of degrees:

- tonical degrees: I, III and VI

- dominantic degrees:VII, V and III

- subdominatic degrees: II, IV and VI

Any degree exists only in relation to an audible harmonic center, called the tonic, symbolized by a I. Relative to this I, other degrees are numbered around it. If another degree than the I forms a temporary harmonic center, this is created by at least one secondary degree, usually a dominant, sometimes accompanied by a subdominant.

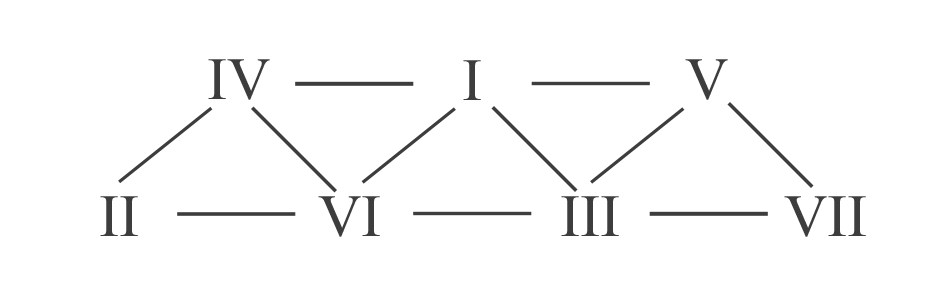

skeleton of basic degrees

There are seven basic degrees: I, II, III, IV, V, VI and VII. In the image above, their mutual relationships are graphically represented like this: a perfect fifth is represented by a horizontal line and a diatonic third is represented by a diagonal line. Degrees a fifth apart have 1 common tone, and degrees a third apart have two common tones.The true neighbors of the I are therefore not the diatonic neighbors II and VII, but the acoustically and functionally related VI and III. In fact, no chord is functionally further removed from any other chord than its direct diatonic neighbors, in the case of I, these are of course II (strongest subdominant), and VII (strongest dominant).

On each degree more than just one possible chord can appear; these so-called altered degrees occur often in various harmonic styles.

Diatonic scale

A diatonic scale is a scale consisting of only whole tone and semitone distances, no other.

Diatonic scales include:

- all church modes

- the melodic minor scale and its derived modes

- several modes from world music traditions

- both octotonic scales

Non-diationic scales include:

- all pentatonic scales

- the harmonic minor scale and its derived modes

- several modes from world music traditions

- the whole-tone scale, also called anhemitonic hexatonic scale

- the chromatic scale

Diatonic systems

There are two diatonic systems, both are based upon basic tones and form a core part of music theory, the two parts are

- the tonal system: the major-minor system, using functional harmony

- the modal system: historically the older, based upon church modes

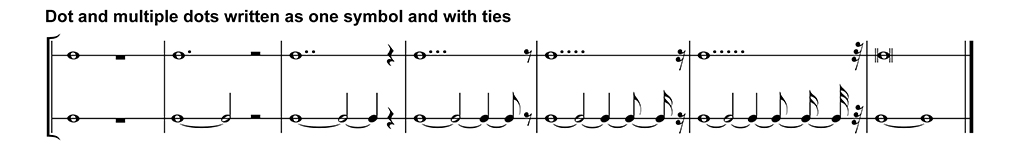

Dot

Definition

A dot (literally: a point) in notation is a symbol to lengthen the duration of a note.

The effect of one dot on a note can be seen in two ways, which have identical results, but arrive at this through different reasoning:

- one dot makes a two-part note three-part (historical explanation)

- one dot makes a not longer by half, 50% longer (modern explanation)

In medieval and renaissance notation dots were amply applied and could indicate a variety of changes to notes, most of which are listed here:

- punctus perfectionis (3-part note, in 3-part timing only)

- punctus additionis (lengthened note, in 2-part timing only)

- punctus augmentationis (another name for punctus additionis)

- punctus syncopationis (syncopated note, rhythmically set apart)

- punctus divisionis (creating unusual rhythmical divisions)

- punctus alterationis (creating a lengthened note 2 notes further)

- punctus imperfectionis (an alternative name for punctus divisionis, in special circumstances)

Still, a dot is a dot, and its symbol is and has always been .

More than one dot

An additional dot, notated next to the other, will add another 50% of the last dot to the duration of a note. 50% of 50% means another extra 25%, or 1/4 of duration. A third dot will add yet 1/8, a fourth 1/16, and so on. In classical music two dots do now and then occur, but for more than two dots to a note one has to look at the 20th century notated repertoire.

It is possible to compare what happens when adding more than one dot to a notehead to the Paradox of Zeno: a note with a long series of dots will come close to approaching its double duration, yet never completely reaching it: 1 + 1/2 + 1/4 + 1/8 + 1/16 + 1/32 + … approaches 2 but never equals it.

It is possible to compare what happens when adding more than one dot to a notehead to the Paradox of Zeno: a note with a long series of dots will come close to approaching its double duration, yet never completely reaching it: 1 + 1/2 + 1/4 + 1/8 + 1/16 + 1/32 + … approaches 2 but never equals it.

Frequency

A frequency is a stable vibration, measured in cycles by time.

The unit of frequency is called Herz, abbreviated by Hz, and is measured in cycles per second:

![]()

Fundamental

A fundamental is a tone that is the harmonic basis of an interval, a chord or even a certain sound.

Harmonic

A harmonic is a higher natural overtone of a tone. The harmonic series (explained below) follows a sequence of whole numbers.

Harmonic Analysis

Definition

Harmonic analysis describes in detail a particular sequence, or progression of tones, intervals, triads or chords.

Transforming the why to how and what

In general, harmonic analysis gives a particular description of how harmony functions in a certain piece of music.

No analysis can ever completely answer why a composition is as it is (was made this way), therefore the basic and often instinctive question for the “why” has to be rephrased in terms of the “what” and the “how“, therefore:

Harmonic analysis asks and answers two main questions:

- what is the harmony made of (composition)

- how is the harmony put together (structure)

More particularly, harmonic analysis can analyse functional harmony precisely by determining tonics, subdominants, dominants and their degrees, whether altered or not.

Harmonic analysis in practice

When applied properly, harmonic analysis is a general tool with which one can approach non-functional harmony as well.

Harmonic analysis always involves specifically trained ears, and cannot ever be done merely on sight from notation. The quality of a harmonic analysis is therefore as good as the brains behind the ears that do the evaluation.

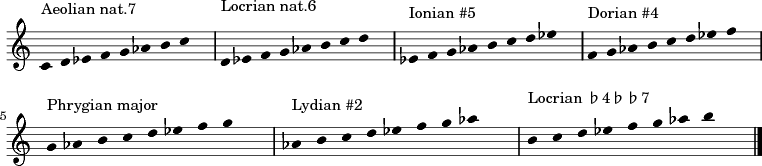

Harmonic minor modes

The harmonic minor modes are modes which can be derived from degrees of the harmonic minor scale.

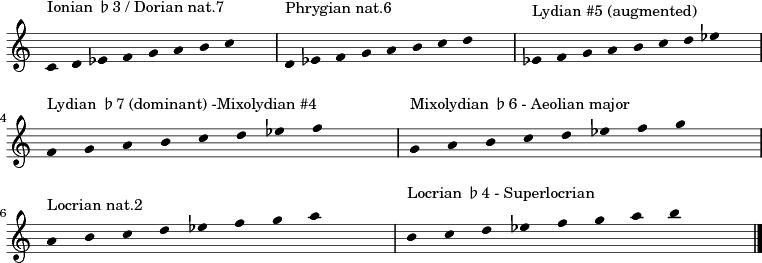

Below the 7 harmonic minor modes can be found in notation on c:

notation of the harmonic modes of c

The harmonic minor modes can be called by the following technically descriptive names, which are based upon comparison with the church modes:

- harmonic minor or aeolian natural 7

- locrian natural 6

- ionian augmented or ionian sharp 5

- dorian sharp 4

- phrygian major, phrygian natural 3 or spanish phrygian

- lydian sharp 2

- locrian flat 4 double flat 7, sometimes also called “altered scale”

Finally these 7 harmonic minor modes are here given all notated on c:

notation of the harmonic modes on c

Harmonic series

Every single tone sounding creates a series of sympathetically sounding overtones. The simplest series of overtones is the harmonic series.

Definition

The harmonic series is a sequence of harmonics, of overtones and a fundamental, ordered and represented by whole numbers and their inversions.

As the harmonic series progresses upwards, the intervals gradually become smaller.

Harmonics 4, 5 and 6 form a major triad; 4, 5, 6 and 7 an approximate dominant seventh chord.

Notation of harmonic series

The harmonic series in music notation below gives an approximation of the pure harmonics 1 through 16, with the help of quarter tones:

Harmony

Harmony is created by the interrelationships of different pitches together in time.

Interval

An interval in music is the sound of exactly two tones sounding together, or one after the other.

- all intervals can be measured by the number of diatonic steps and by their semitone distances;

- more technically, an interval can also be described as a frequency ratio relationship between two stable vibrations;

- all intervals can occur on (above or below) all tones;

- we speak of a harmonic interval when the two tones sound at the same time;

- we speak of a melodic interval when the two tones sound one after the other;

- we speak of a basic interval when it is not larger than an octave;

- we speak of a wide interval when it is larger than an octave.

Nomenclature of intervals

All intervals are described by a counting word, some of which are taken from Italian. The exact nature of an interval can however only be determined by two factors: the distance and the quality of the interval.

- The distance, or diatonic distance, giving the basic name:

- unison – two identical tones, symbolized by the number 1

- second – two tones 1 step apart, symbolized by the number 2

- third – two tones 2 steps apart, symbolized by the number 3

- fourth – two tones 3 steps apart, symbolized by the number 4

- fifth – two tones 4 steps apart, symbolized by the number 5

- sixth – two tones 5 steps apart, symbolized by the number 6

- seventh – two tones 6 steps apart, symbolized by the number 7

- octave – two tones 7 steps apart, symbolized by the number 8

- The quality, or chromatic distance, giving the exact name attached before the basic name:

- perfect – only for unison, fourth, fifth and octave, symbolized by capital P

- major – the large version of a second, third, sixth and seventh, symbolized by capital M

- minor – the small version of a second, third, sixth and seventh, symbolized by minuscule m

- augmented – a larger version of a perfect or major interval, symbolized by capital A

- diminished – a smaller version of a perfect or minor interval, symbolized by minuscule d

Basic intervals

A basic interval is an interval from a unison up to an octave, not larger.

The distance or diatonic distance is counted in steps of a scale, while the quality or chromatic distance is counted in semitones, resulting in the following order of basic intervals by size:

| size | -1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 |

| interval | d1 | P1, d2 | m2, A1 | M2, d3 | m3, A2 | M3, d4 | P4, A3 | A4, d5 | P5, d6 | m6, A5 | M6, d7 | m7, A6 | M7, d8 | P8, A7 | A8 |

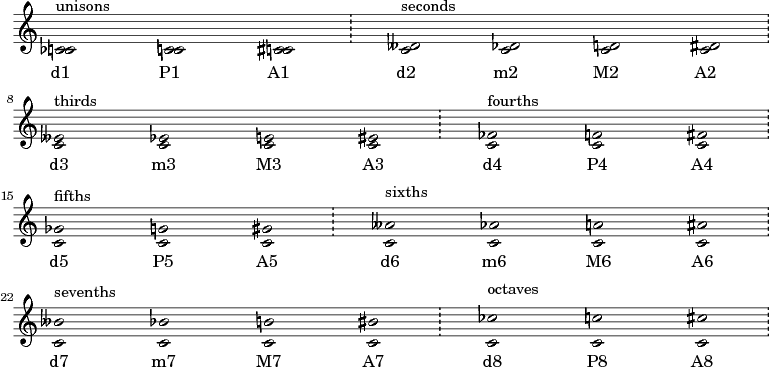

A summary of all possible basic intervals by name is given here in notation:

Perception of the interval

The unique sound of each interval can be immediately recognized by hearing, making it in fact a truly fundamental element of all music.

When listening to two simultaneous tones, their pitches and frequencies mix and react, creating even more tones sounding together: interference tones. This complex of tones becomes one comprehensive sound, and the individual pitches become acoustically more or less absorbed into the human perception of the single interval: the interval itself is in fact perceived as louder than the individual tones it consists of. It is human perception which “summarizes” the tones into the single interval, but it has good acoustic reasons to do so. Thus the interval is equally the basic prerequisite for all melody as it is for harmony.

Wide intervals

Wider than the octave, music theory describes the larger, wide intervals. Though similar to, all of these intervals sound rather different than their related basic intervals, which is why the popular term “compound interval” is inaccurate and to be avoided here. These wide intervals do not consist of two sounds, and hence are not “compound sounds”, but original sounds, intervals in their own right. They are related though, and found in a way actually identical to the process of inversion: the repositioning of one of the two tones in another octave postion.

| basic interval | wide interval |

| 2 | 9 |

| 3 | 10 |

| 4 | 11 |

| 5 | 12 |

| 6 | 13 |

| 7 | 14 |

| 8 | 15 |

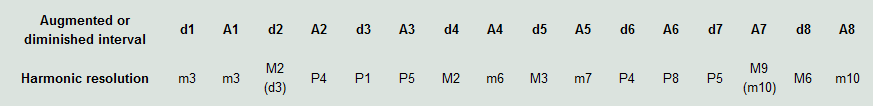

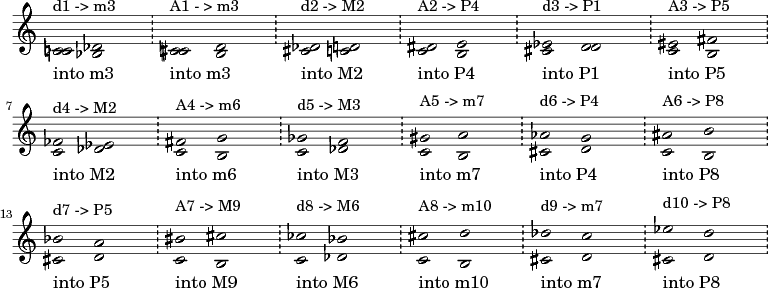

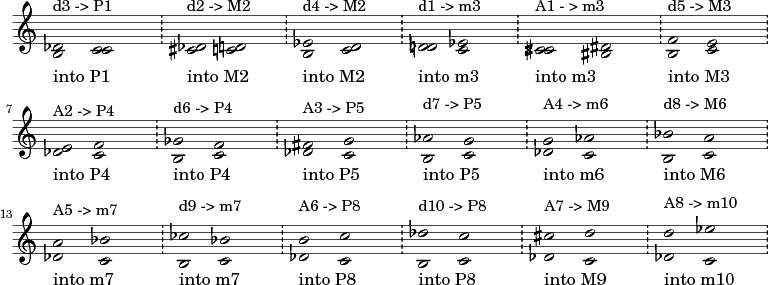

Augmented and diminished intervals and their harmonic resolutions

The tension of dissonance in augmented and diminished intervals can be led into resolution with relative consonance by treating the constituent tones as voices and resolving each by a minor second (not just any chromatic semitone, but a precise minor second) in opposite directions.

The respective resolutions are found as follows:

- The tension in an augmented interval is caused by the widening, so resolution is found widening further outwards.

- The tension in a diminished interval is caused by the narrowing, so resolution is found narrowing further inwards.

The following tables summarizes the results:

In notation below are summarized all augmented and diminished intervals with resolutions ranging from unison up to and including the octave; all dissonances are here on c:

In notation below are summarized all augmented and diminished intervals with resolutions ranging from unison up to and including the octave; all dissonances are here on c:

The same intervals once again, now in order of the number of semitones in their resolutions; all resolutions are here on c (or an enharmonic equivalent):

In these augmented and diminished intervals and their resolution, we are able to as it were hear the microscopic forces of functional harmony; they can be and are in fact used both as harmonic and melodic intervals. Careful study of these is highly recommended for the professional musician, as they allow for ‘listening on the inside of harmony’.

In these augmented and diminished intervals and their resolution, we are able to as it were hear the microscopic forces of functional harmony; they can be and are in fact used both as harmonic and melodic intervals. Careful study of these is highly recommended for the professional musician, as they allow for ‘listening on the inside of harmony’.

Inversion

In music, the word inversion always means the same harmonic content, but in a different position.

The term is used for:

- intervals: 2 possible positions, so 1 possible inversion each

- triads: 3 possible positions, so 2 possible inversions each

- seventh chords: 4 possible positions, so 3 possible inversions each

- melody: all intervals change direction, this can be done diatonically (not changing the scale) or chromatically (not changing the intervals)

- 12 tone row: all intervals change direction while keeping the intervals chromatically identical

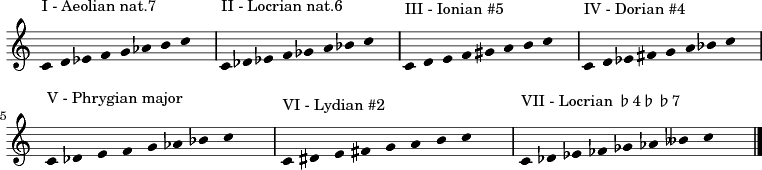

Melodic minor modes

The melodic minor modes are modes which can be derived from degrees of the melodic minor scale.

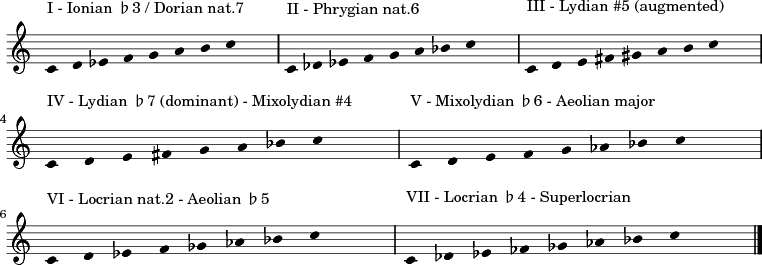

Below the 7 melodic minor modes of ccan be found in music notation:

melodic minor modes of c

The melodic minor modes can be called by the following technically descriptive names, which are based upon comparison with the church modes:

- melodic minor, ionian minor or ionian flat 3, dorian natural 7

- phrygian natural 6 or dorian flat 2

- lydian augmented or lydian sharp 5

- lydian dominant or lydian flat 7, mixolydian sharp 4, sometimes jokingly called “lyxomidian”

- aeolian major or aeolian natural 3, mixolydian flat 6

- locrian natural 2, aeolian diminished or aeolian flat 5

- superlocrian or locrian flat 4

Finally these 7 melodic minor modes are here given all notated on c:

melodic minor modes on c

Melody

Melody is created by a sequence of different pitches in time.

Minuscule

Definition

A minuscule is a lower case letter, and the opposite of a capital.

In music, a minuscule can be used to represent a single tone or a (usually minor) key.

Example of alphabets in minuscules

- abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz

- αβγδεζηθικλμνξοπρσςτυφχψω

- абвгдежзийклмнопрстуфхцчшщъыьэюя

Mode

Definition of mode

A mode, like a scale, is a collection of tones arranged in a stepwise ascending or descending order, generally spanning one octave.

More than a scale, in musical practice, a mode can have specific melodic requirements for performance, such as a specific order of playing the pitches involved in a makam or raga. Music based on the use of modes is generally called modal music, and though not excluding the use of harmony, this term is generally used in opposition to music “powered” by functional harmony, which is called tonal music.

Different modes

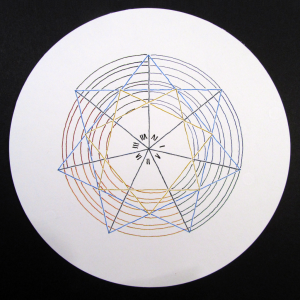

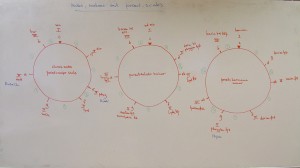

mode types as tone circles

Different modes can start and end on different tones or tonics, and alteration of tones can be used to achieve an even greater variety of modes. There are numerous modes used throughout the world, sometimes with different ascending and descending scales.

Some of these modes can be found in this reference guide, such as the church modes, the harmonic minor modes, the melodic minor modes (these three types can be seen in the whiteboard image, represented as tone circles, derived from the circle of seconds), and modes like the thaats from India.

There exist however many more modes, but these fall outside the scope of this page. Examples are the scales of the many Indian ragas as wel as the hundreds of modes (makams) in Ottoman and Arabic music (maqams), which deserve separate treatment.

Music

Music is sound and silence, performed by musicians.

Music can mostly be symbolized by notation.

Notation

Definition

Notation, or music notation, is the written or printed visualization of what a performer needs to do to produce a certain piece of music. Notation indirectly represents music, by using a system of visual symbols.

Symbols for performance

Notation does not directly symbolize sound nor what can be heard, but rather that which has to be performed, so that as a result sound is indirectly symbolized. Notation captures precise actions to produce sounds: notation is music that can be seen and read, and can thus be transferred in time or space so others can learn a piece of music without directly copying or even hearing another’s, among which a composer’s or a teacher’s, playing.

Notation eventually also in part implies writing down what is to be percieved, what is to be heard. In this sense, notation means writing down what can be heard (both internally as imagination and externally as perception) for the reading, playing or performance, by other musicians, with symbols for sounds, tones and silences.

Reading vs decyphering

There is a huge difference between being able to decypher and being able to read musical notation, the same difference as exists basically between being able to decypher (translate) or truly read languages (yet, aoccdrnig to a rscheearch at Cmabrigde Uinervtisy, it deosn’t mttaer in waht oredr the ltteers in a wrod are, the olny iprmoatnt tihng is taht the frist and lsat ltteer be at the rghit pclae. The rset can be a toatl mses and you can sitll raed it wouthit porbelm. Tihs is bcuseae the huamn mnid deos not raed ervey lteter by istlef, but the wrod as a wlohe).

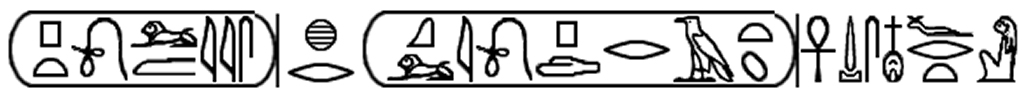

There is therefore a difference between the ability to decypher or to read, for example this 何この諺にお読みください , or this 이게 말합를 참조하시기 바랍니다 , or this 請閱讀本說什麼 , or this يرجى قراءة هذا ما تقول , or even this language below:

For a musician using musical notation, one has to be able to fluently read it. The ability to read musical notation can vary from being able to read the notes (aloud, by name) to being able to sing or play (a part of) them, or even a whole score, or when necessary intelligently summarizing the essential into something audibly acceptable, to being able to silently read it “aloud in one’s mind”: to listen to the music written in one’s imagination.

The ability to read fluently is essential for musicians who make (extensive) use of written music.

Forms of musical notation

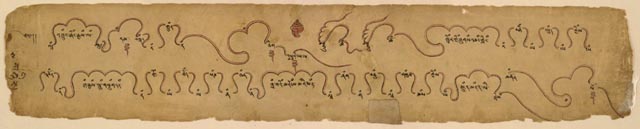

Tibetan music notation

Notated music is also called sheet music.

Worldwide there are and have been various forms of musical notation, each specific for the world music tradition it has or had been developed for, each emphasizing certain important elements and leaving out others. All systems were in their oldest forms developed by performers, some were later developed further by composers; most use a set of 5 or 7 basic tones.

The system of notation as used in European music in the 19th century has spread worldwide, and has been adopted by and for many different traditions and styles.

Chinese Guqin musical notation

Based on this system, slightly differing contemporary notations have developed such as:

- Jazz notation

- Turkish notation

Examples of notation of completely different classical music traditions are:

- Chinese notation

- European mensural notation

- Indian notation

- Japanese notation

Note

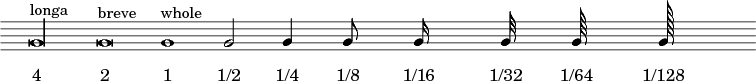

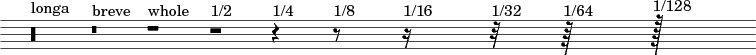

A note in musical notation is a written symbol that represents the relative duration of a sound or tone.

The example below shows a range of note-values, ranging from very long to very short durations.

The position of a notehead on a staff determines its pitch, depending on the clef used. A note must therefore always contain a notehead, and most notes have also a notestem.

Notehead

A notehead is the almost egg-shaped part of a (written) note.

There exist various shapes of noteheads, all have specific meanings, which depend on their use. Mostly these are used for rhythmical (e.g. black or white) or musical instrumental purposes (e.g. cross, plus, or white and black diamond).

Notestem

A notestem in musical notation is a thin vertical line attached to a notehead. The notestem can point up- or downwards, depending on the relative position of the note on the staff.

Overtone

An overtone is a subtly sounding together with a performed tone, but higher and part of the timbre of it. Not all overtones are also harmonics, nor do all fit in the harmonic series.

The opposite of overtones are undertones, many of which are caused by acoustics.

Pitch

A pitch is a single sounding frequency; in music, a pitch is also called a tone.

In notation pitches are notated as notes on a staff, using a particular clef.

Polyphony

Polyphony is the detailed construction of simultaneous melodies within a consistent harmonic style.

Quarter tone

A quarter tone is a microtonal alteration, exactly half of a semitone.

Quarter tones occur in world music and are sometimes used in modern notation. As is so often the case with contemporary additions to musical notation, there is no generally fixed standard for notating them. One of the systems used, also used by notation software, is given below and the examples show the ascending and descending scales of c in quarter tones. Each bar spans a whole tone in four equal steps:

Range

Range in music can have two distinct meanings:

- Range of pitches for a musical instrument, meaning the range of an instrument from its lowest to its highest possible pitches, also called an instruments’ ambitus

- Sounding range, indicating the distance a particular sound can still be heard (rarely)

Rest

A rest, or pause, in musical notation indicates a relative duration of performed silence, i.e. where no sound is produced by one or more musicians.

A rest does not mean the musician’s attention may waver from the music. Performed silences have audible beginnings and endings just like tones, especially the shorter values, and in the absence of sound any superfluous random noise or even bodily movement may distract the audience.

The example below shows a range of rest-values, ranging from very long to very short durations.

The positions of rests on staves are more or less fixed as given in the example above. Except in compact polyphonic notation (see the outline of basic music theory), where they will visually float with the melodic layers they belong to, rests should be notated as given here.

Scale

A scale is a collection of tones arranged in a stepwise ascending or descending order, usually spanning one octave, exceptionally spanning two.

All scales consist of a series of (ascending or descending) seconds, with sometimes a (minor) third included. Generally a scale has at least 5 tones (with less it is rather a chord), and no consecutive thirds. Most common scales have 7 tones, but scales with more tones exist as well. In some world music traditions, there are scales containing microtonally different versions of a particular step (or degree), so the number of possible tones in a scale is actually quite large.

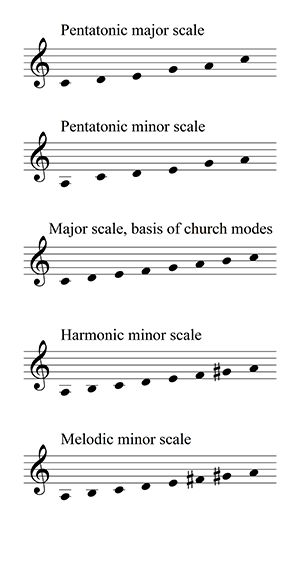

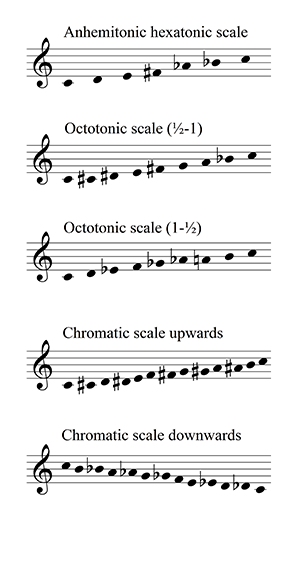

In the examples above, two sets of common scales are given, all on a fundamental c. The first image contains well know basic scales, the second image contains some slightly more advanced scales.

Different scales can start and end on different tones or tonics, and alteration of tones can be used to achieve an even greater variety of scales. There are numerous scales used throughout the world, sometimes with different ascending and descending scales.

The concepts scale and mode are closely related, but not identical. E.g. a scale is not always a mode, yet a mode can always be presented by a scale, or part of it.

Parts of scales have their own special names in music theory:

- trichord – a 3 tone segment of a scale

- tetrachord – a 4 tone segment of a scale

- pentachord – a 5 tone segment of a scale

- hexachord – a 6 tone segment of a scale

See also:

Score order

Score order in musical notation is the normal vertical order of instruments and their staves in a score.

Score order may vary per style and group; a Jazz bigband e.g. has its own particular score order, yet in general it can be said that score order is achieved by two general criteria:

- Staves are grouped by type of musical instrument (e.g. brass instruments in 1 group);

- Staves are ordered by instrument register, the higher above the lower instruments.

Below you find a general list of score order in a symphony orchestra (from top to bottom):

- Woodwind instruments

- flutes (ranged from high to low)

- oboes (ranged from high to low)

- clarinets (ranged from high to low)

- bassoons (ranged from high to low)

- French Horns

- Brass Instruments

- trumpets (ranged from high to low)

- trombones (ranged from high to low)

- tubas (ranged from high to low)

- Percussion

- Possible SOLO instruments for solo concertos (inserted just above the string section)

- Strings

- violins I

- violins II

- violas

- celli

- contrabasses

Semitone

A semitone is the smallest basic interval used in the diatonic system; it is also called: a half step.

The following intervals contain 1 semitone:

- minor second (in both directions)

- augmented unison (upwards)

- diminished unison (downwards)

A series of semitones in one direction forms a special scale: the chromatic scale.

Seventh chord

Definition of seventh chord

A seventh chord is a special type of chord which consists of 4 different tones, constructed on a fundamental in consecutive thirds upwards.

The tones of a seventh chord are numbered 1-3-5-7.

Composition of seventh chords

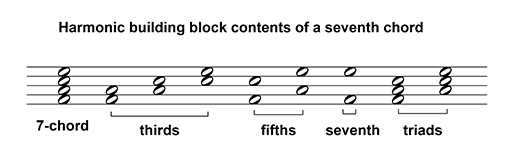

A seventh chord is itself a building block but it is constructed out of building blocks as well:

- a seventh chord consists in its basic form of 6 intervals

- 3 thirds (1-3, 3-5 and 5-7)

- 2 fifths (1-5 and 3-7)

- 1 seventh (1-7)

- a seventh chord consists in its basic form of 2 triads

- the fundamental triad 1-3-5

- the upper triad 3-5-7

The composition of a seventh chord, shown in general notation without clef will look like this:

If the seventh chord is in inversion it contains inversions of these intervals and triads.

Inversions of seventh chords

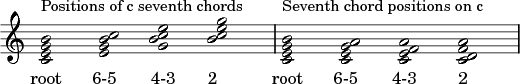

A seventh chord is still considered to be the same seventh chord when the 4 tones it consists of are presented in another position than the basic 1-3-5-7 described so far. There are four basic positions for a seventh chord:

- The 1 is the lowest tone, this is called root position, short: 7

- The 3 is the lowest tone, this is called first inversion or 6-5 position, short: 6-5

- The 5 is the lowest tone, this is called second inversion or 4-3 position, short: 4-3

- The 7 is the lowest tone. this is called third inversion or 2 (second) position, short: 2

The acoustic properties are similar but somewhat different, and these positions can be perceived as derived from one basic structure.

The examples below are basic positions of seventh chords of c and on c, without alterations.

Types of seventh chords

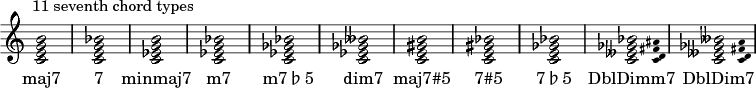

There are 11 types of seventh chords:

- Major seventh: consisting of

- a major triad and a minor triad

- a major third, a minor third, a major third, two perfect fifths and a major seventh

- Dominant seventh: consisting of

- a major triad and a diminished triad

- a major third, a minor third, a minor third, one perfect fifth, one diminished fifth and a minor seventh

- Minor seventh: consisting of

- a minor triad and a major triad

- a minor third, a major third, a minor third, two perfect fifths and a minor seventh

- Minor major seventh: consisting of

- a minor triad and an augmented triad

- a minor third, a major third, a major third, one perfect fifth, one augmented fifth and a major seventh

- Half diminished: consisting of

- a diminished traid and a minor triad

- two minor thirds, a major third, one diminished fifth, a perfect fifth and a minor seventh

- Diminished seventh: consisting of

- two diminished triads

- three minor thirds, two diminished fifth and a diminished seventh

- Augmented seventh: consisting of

- an augmented triad and a major triad

- two major thirds, a minor third, an augmented fifth, a perfect fifth and a major seventh

- Augmented dominant: consisting of

- an augmented triad and a flat 5 triad

- two major thirds, a diminished third, an augmented fifth, a diminished fifth and a minor seventh

- Flat 5 dominant: consisting of

- a flat 5 triad and a double diminished triad

- a major third, a diminished third, a major third, two diminished fifths and a minor seventh

- Double diminished minor seventh: consisting of

- a double diminished triad and an augmented triad

- a diminished third, a major third, a major third, a diminished fifth, an augmented fifth and a minor seventh

- Double diminished seventh: consisting of

- a double diminished triad and a major triad

- a diminished third, a major third, a minor third, a diminished fifth, a perfect fifth and a diminished seventh

These seventh chords can occur on any tone, the examples below show all 11 seventh chords (in root position) of c in musical notation:

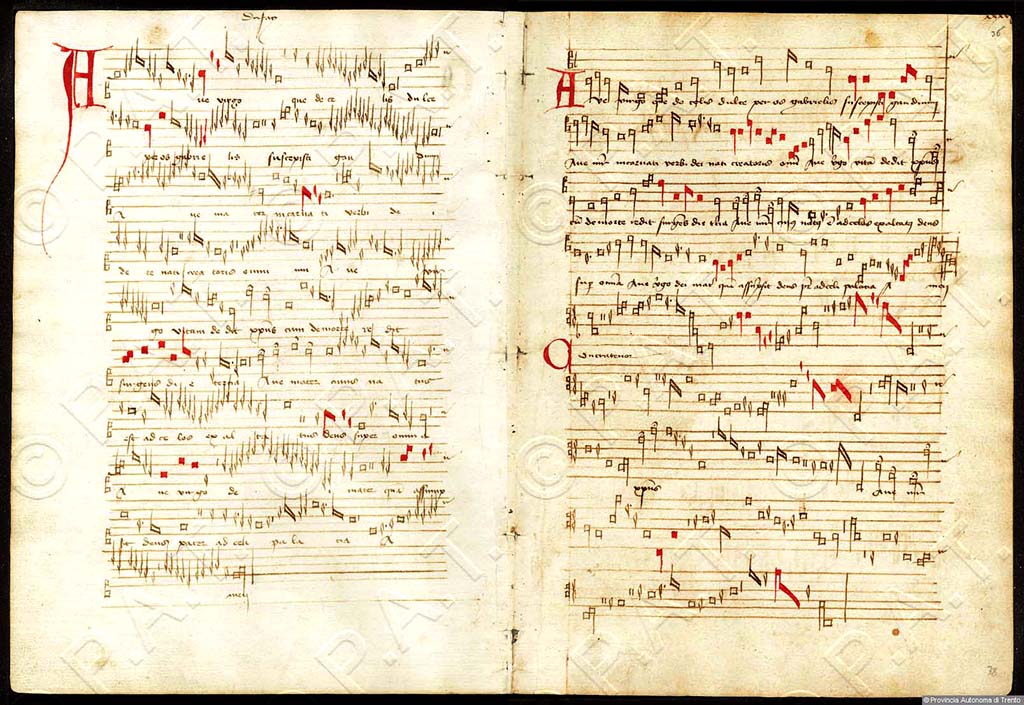

Sheet music

XV century sheet music, containing (three) parts, no score (as was customary at that time)

Sheet music is music notated on music paper.

Sheet music is mostly either a score or a part, or a section of these.

Sheet music can be printed or hand-written.

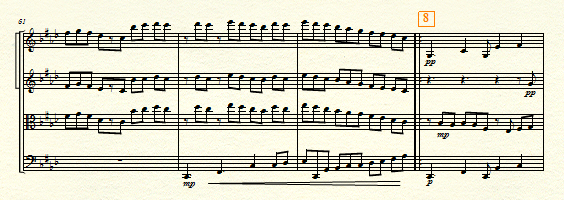

example of modern score: section of the score of my string quartet nr.3

Part

In music, a part, is a part of a score, and indicates the (excerpted) sheet music that is played by an individual musical instrument or instrumentalist.

Score

In music, a score provides a complete notated version of a composition.

In a score today, all the parts are written together in one system of staves, for a composers’ overview or for use by a conductor.

Silence

Silence is the opposite of sound. As true silence can only exist without a medium for vibrations, silence in practice can be considered to be the relative absence of sound, as perceived by our hearing.

In music, silence is always performed, and never the mere absence of sound. Silence is as essential for music as sound is.

In notation, silence is symbolized by rests.

Sound

Definition

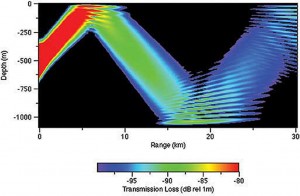

Sound is the perceived complex phenomenon of vibrations traveling as pressure waves through a medium. For all living beings on earth this medium is either air or water. Such vibrations are called sound when they are perceived by (our) hearing.

sound travelling underwater

There are thus three components in sound: vibration, medium, hearing. Generally, silence is considered to be the opposite of sound.

Example of sound

Press the button to play and listen to a 14 seconds example of a sound.

Sound in music

A musical sound can be recognized and defined by the following 5 parameters:

- pitch (or frequency)

- duration (or relative rhythmic value)

- timbre (sound color or instrument)

- dynamics (loudness)

- position in space (relative to the listener)

All music consists of related sounds and silences, which can be symbolized by notation.

Staff

A staff in musical notation normally consists of 5 parallel horizontal lines.

In music history, the staff evolved from 3 to 4, and eventually 5 and even 6 lines, before being brought back and fixed to the number of 5 lines. The reason for this is probably that the human brain can immediately recognize a quantity of 5 without need for counting, so with the use of 6 lines immediate recognition of pitch became more difficult; instead ledger lines were invented for pitches outside the staff.

Though more than 5 lines remains suffuciently rare, special notation, such as for percussion, can however still employ staves consisting of a different number of lines, even only of 1 line (for bass drum or tamtam).

At the beginning of most staves a clef is employed to determine its exact usage, and to determine the pitches notated.

Timbre

Timbre can best be described as color of and within sound, and can be measured physically as a dynamic conglomerate of frequencies.

Timbre is in integral part of any sounding tone, and consists of harmonics and other overtones. By their timbre, we can distinguish various musical instruments.

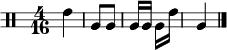

Time signature

A time signature creates a regular metric grouping of music in time, both audibly (rhythm) and visually (in musical notation).

A time signature consists of two numbers, one above the other, without a horizontal line between them (it is not a fraction). The upper number indicates the number of beats, the lower number represents the note value used to count. Although time signatures using the quarter or eighth notes as basis are more common, theoretically many more are possible, and indeed sometimes used. The most common time signatures are two-four, three-four, four-four and six-eight.

With the use of time signatures, the notes become grouped in units called bars or measures, each group separated from the next by a vertical line, called the barline.

Binary time signatures

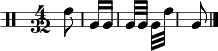

Binary time signatures have a regular subdivision of 2 accents within each beat, independent of the number of beats per bar. The examples below show the strucure of the most commonly used binary time signatures:

![]()

![]()

![]()

Ternary time signatures

Ternary time signatures have a regular subdivision of 3 accents within each beat, independent of the number of beats per bar. The examples below show the strucure of the most commonly used ternary time signatures:

![]()

![]()

![]()

Choosing a time signature

Choosing a time signature first of all affects the flow of the music itself, but it also plays a role in the legibility of the musical notation: the ease with which it can be read and performed. Finally, it also affects the way a performer innerly experiences time.

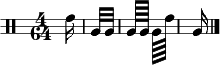

The following examples are collected for purpose of theoretical demonstration: to show how one rhythm can be notated with different note values, so all these examples notate the exact same rhythm, but with the help of different notes.

Normally a rhythm like this would rather be notated in either 4\4 or 4\8, depending on the tempo intended, for purely practical reasons of performance. This is to avoid too many symbols in notation. It is however a choice the notating person, whether composer or transcriber, can and has to make.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Tone

A tone is a sound which can be perceived as a single pitch.

Transposition

Transposition is the shifting of musical notation by a certain specific interval.

Commonly occurring reasons to transpose music are:

- to correctly write the staff or part for a transposing musical instrument

- to fit the music to the ambitus (range) of a particular instrument

- to fit the music to the range of a particular singer or voice

- to change the key of a (part of a) piece of music

Triad

Definition of triad

A triad is a special type of chord which consists of 3 different tones, in consecutive thirds upwards.

The tones of a triad are numbered 1-3-5.

Composition of triads

A triad is itself a building block but it is constructed out of building blocks as well: a triad consists in its basic form of three intervals: 2 thirds and 1 fifth (or their respective inversions).

Inversions of triads

A triad is still considered to be the same triad when the 3 tones it consists of are presented in another position than the basic 1-3-5 described before. There are three basic positions for a triad:

- The 1 is the lowest tone, this is called root position

- The 3 is the lowest tone, this is called first inversion or 6 (sixth) position, short: 6

- The 5 is the lowest tone, this is called second inversion or 6-4 position, short: 6-4

The acoustic properties are similar but somewhat different, and these positions can be perceived as derived from one basic structure.

Types of triads

There are 6 types of triads.

- Major triad: consecutively consisting of

- a major third

- a minor third

- a perfect fifth

- Minor triad: consecutively consisting of

- a minor third

- a major third

- a perfect fifth

- Augmented triad: consecutively consisting of

- a major third

- a major third

- an augmented fifth

- Diminished triad: consecutively consisting of

- a minor third

- a minor third

- a diminished fifth

- Flat 5 triad: consecutively consisting of

- a major third

- a diminished third

- a diminished fifth

- Double Diminished triad: consecutively consisting of

- a diminished third

- a major third

- a diminished fifth

These triads can occur on any tone, the examples below show all 6 triads (in root position) of c in musical notation:

Value-flag

A value-flag is a symbol attached to the notestem of notes (and rests) with a value smaller than a quarter note.

Vibration

vibrations and interference

Vibration is movement without deplacement. Vibration is movement or oscillation within an object itself or in a medium (such as air), in one place.

Vibration, sound and frequency

At the origin of all sound is an object and/or medium which is stirred into vibration.

- a tone or pitch is a relatively simple set of regular vibrations

- a chord is a relatively complex set of regular vibrations

- a noise is a set of (mostly) irregular vibrations

Vibrations are measured by their frequencies.

The study of sound and vibration are closely related. Sound creates pressure waves in a medium, and these pressure waves can induce the vibration of the ear drum. The harmonic series are a sound phenomenon directly related to vibration itself.

Examples of a drum in vibration

The following examples show a drum skin vibrating in 9 different timbres, with varying overtones, ranging from simple to complex:

See also

- Outline of basic music theory

- Students categorizing music

- Music paper

- World music

- Tools for students

External links

- GNU solfege (free music education software)

- Understanding basic music theory free online beginners’ course recommended by www.openculture.com (several download formats)

- www.musictheory.net by Ricci Adam, including online exercises