Professional preparatory music theory: Basic elements of music theory.

Chapter 2 of the Basic elements of music theory – by Oscar van Dillen ©2014-16

The advanced learning book can be found at Outline of basic music theory.

Pages and chapters:

Chapter 1: Introduction

Chapter 2: Musical notation

Chapter 3: Building blocks of harmony – Scales

Chapter 4: Building blocks of harmony – Intervals

Chapter 5: Building blocks of harmony – Chords

Chapter 6: Keys and key signatures

Chapter 7: Further study

Musical notation

- Musical notation is used to write or print sheet music for performance.

In a strict sense the words note and tone do not have the same meaning. Both can be notated, but a note is notated by its shape, and a tone by its vertical position on a staff. A note indicates a time value of relative duration, a tone indicates a pitch, a stable frequency of sound. Although musical notation uses both at the same time: notes are needed to notate rhythm, as tones are needed to notate melody and harmony.

Note and rest values

- A note is the relative rhythmical value of a duration of a sound.

- A rest is the relative rhythmical value of a duration of a silence.

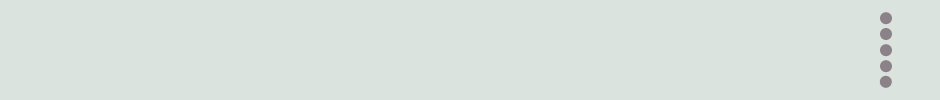

Most written or printed music today makes use of a small set of notes, ranging from the whole note to the 1/16 note. To indicate silence, a set of corresponding rests exists as well.

The system of notation of durations works by double and half values. Two 1/2 notes or rests, add up to the same duration as a whole note or rest (two rests add up to a longer silence, but two notes generally mean two sounds, so it is not always identical); two 1/4 notes add up to the same duration as a 1/2 note; two 1/8 notes add up to the same duration as a 1/4 note; two 1/16 notes add up to the same duration as a 1/8 note; see and hear example 1 which compares and demonstrates this:

example 1 – most used note and rest values

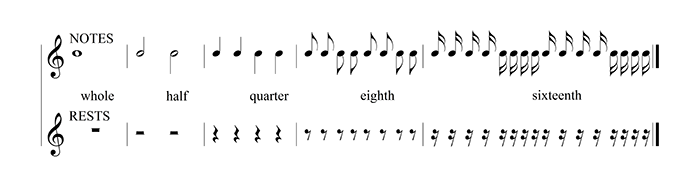

In the example above, alternate directions are notated in the notestems, half of them are notated upwards and half downwards, and this suggests some grouping. Normally, stem directions depend on the position of a note on a staff: when it is high, the stem goes down, when it is low, the stem goes up. To more clearly show the rhythmical groupings, notes are always beamed together per beat, this means that the values flags are written as horizontal lines, as in the example below. In example 2, the exact same order is notated as before, but now graphically improved for reading:

example 2 – note values with beams

Time signatures

- A time signature is a regular grouping of notes to a metric background for notation.

Most sheet music is notated in either 2/4, 3/4, 4/4 or 6/8 time signature. A time signature groups notes into a certain number of beats, and also implies a subdivision of each beat.

Binary time signature

There are 2 beats in a 2/4, 3 beats in a 3/4 and 4 beats in a 4/4 time signature. The upper number here indicates a number of beats, and the lower number indicates the 1-beat note (quarter note). These time signatures are also called binary (meaning: in 2), as each beat subdivides into 2. The basic note values of musical notation represent a binary system, as demonstrated in examples 1 and 2 above. In notation, the groups are called bars and are separated by vertical barlines. A piece of music always ends with a double barline.

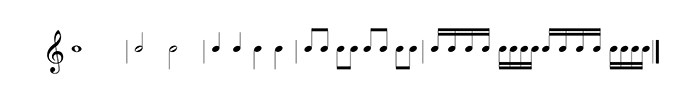

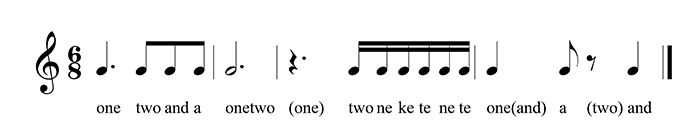

A simple rhythmic phrase, using the binary 2/4 (pronounced two four) is given in example 3:

example 3 – simple rhythm in 2/4 with possible vocalizations

Note that in typing one writes 2/4, with a slash or line keeping the two numbers apart, but in musical notation no such (horizontal) line is written.

EXERCISES 1

To practice such rhythms, I developed a series of exercises, called Rhythmic Building Blocks. This website contains two such pages in pdf, one for the binary time signature of 2/4, here it is:

Important is how to practice this, here are my recommendations:

- always use a metronome, start with slow tempi and build up gradually;

- in the beginning, just singing, tapping or clapping is sufficient;

- when some proficiency is attained, singing while tapping the beat is recommended;

- when still more proficiency is attained, tapping while counting the beats becomes possible;

- the three steps described above are progressively difficult;

- the exercise consists of 2 bar phrases, each must be repeated at least once.

If one understands how a 2/4 time signature “works”, a 3/4 and 4/4 are merely somewhat longer versions of the same thing, and should offer no special problems in reading.

Ternary time signature

A ternary time signature can also have 2, 3, 4 or even more beats per bar, but the difference lies in the subdivision of each beat: in three instead of in two. To keep these visually apart, they are written with the shorter note value of an eighth note, such as 6/8 (two ternary beats), 9/8 (three ternary beats), and 12/8 (four ternary beats). In this way, each beat consists of three “subbeats”, and is therefore ternary. The 1/8 note does note represent the beat here, but the “subbeat”: the underlying smaller value within each beat. Much blues music has a ternary feel.

A simple rhythmic phrase, using the binary 6/8 (pronounced six eight) is given in example 4:

example 4 – simple rhythm in 6/8 with possible vocalizations

As you can observe, the ternary notes and rests are notated with a dot · next to them. Such a dot makes a note or rest ternary (in three parts), or one can say that it adds 50%.

EXERCISES 2

To practice such rhythms, there is also a page with ternary Rhythmic Building Blocks in 6/8:

Important is how to practice this, here are my recommendations again:

- always use a metronome, start with slow tempi and build up gradually;

- in the beginning, just singing, tapping or clapping is sufficient;

- when some proficiency is attained, singing while tapping the beat is recommended;

- when still more proficiency is attained, tapping while counting the beats becomes possible;

- the three steps described above are progressively difficult;

- the exercise consists of 2 bar phrases, each must be repeated at least once.

If one understands how a 6/8 time signature “works”, a 9/8 and 12/8 are merely somewhat longer versions of the same thing, and should offer no special problems in reading.

Next, and simultaneously in your practicing, you should also study the notation of tones, practicing the reading and writing, and the hearing and singing skills, which are at the core of music theory.

Pitch and tone

- A tone is the relative harmonic value of a pitch.

Basic tones

Internationally there are two systems of names for the basic tones:

- the older system: do, re, mi, fa, sol, la, si

- the newer system: c, d, e, f, g, a, b

These two systems indicate the exact same basic tones: do=c, re=d, mi=e, fa=f, sol=g, la=a and si=b. In English language music theory literature, the second system is always used, so this will also be used here.

The 7 tones c, d, e, f, g, a, and b are called the basic tones.

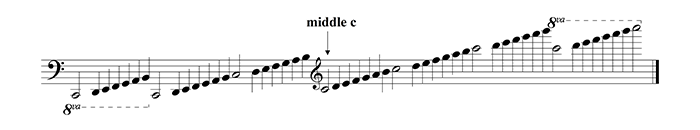

To notate pitch, a 5-line staf is used, plus a clef to indicate the register. In example 5 you can hear and see the basic scale of C over almost the full range of musical registers:

example 5 – basic c scale in all registers

The example above starts with a bass clef (also: f-clef) for three octave registers, and then the clef changes to treble clef (also: g-clef) just before the middle c. When listening to this example, we hear seven times the scale c d e f g a b in different registers, also called octaves. The eight note is the audible repetition of the same tone in a higher register 1=c, 2=d, 3=e, 4=f, 5=g, 6=a, 7=b and finally: 8=c. This eighth note is the octave. The word octave is derived from the Italian word ottava, meaning 8th. 8va is an abbreviated symbol (of otta=8 plus va) for purposes of notation, which you can see in example 5 where it is used for octavating the first seven tones down, and the very last eight up.

A second observation is that any tone is either through (also called: on) a line, or between two lines of the staff. In this way it can be seen at a glance which tone is notated. The five lines of the staff correspond to the number of fingers of one hand: the largest whole number all of us can immediately recognize without counting. When a tone is higher or lower than can be notated on the staff, extra lines are added to the notehead, these are called: ledger lines. They are slightly harder to read, and certainly require experience to recognize at a glance.

EXERCISES 3

It is important to practice this, here are my recommendations:

- practice reading until your reading in both bass- and treble clef are about the same speed, but start by practicing them one by one;

- copy sheet music neatly by hand, and then also in notation software;

- when you do a good job, your handwriting should look more attractive than the computerwork;

- do this at least once a week until you are fluent and you have developed a personal but clearly legible handwriting, just as with writing language.

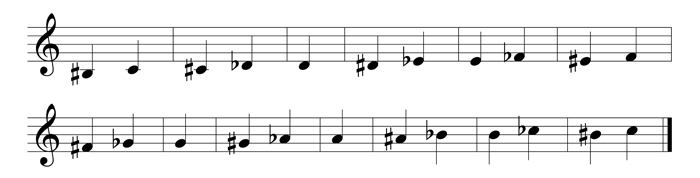

Accidentals and enharmonic equivalence

Basic tones are called by simple letters, but these can be raised and lowered by special notation signs, the accidentals: flat and sharp. The white keys of a keyboard represent the basic tones, the black ones the alterations.

example 6a – keyboard layout with tone names

As can be clearly seen, the black keys have two names: one by lowering (flat or ♭) and one by raising (sharp or ♯). The two names are enharmonically equivalent: sounding the same but a different name.

Flat is sometimes represented by the letter b on a computer keyboard, whereas something like the sharp is already on the computer keyboard as the hashtag sign #. Each octave has 7 basic tones plus 5 alterations, which make up a total of 12 chromatic tones.

Two tones which are named differently but have the same sound or pitch are called enharmonic equivalences. They are enharmonically the same:

example 63 – enharmonic equivalence

The pronunciation of the altered tone names is in reverse order as in notation:

- in notation, an accidental is placed before the tone: to the left therefore;

- in naming, the tone name always comes first: c-sharp, d-flat, d-sharp, e-flat etc.

In sheet music, flats and sharps appear either just before tones, or at the beginning of the staff at the clef as a key signature. Sharps and flats at the clef as a key signature are always at fixed positions, indicating a key signature, to be treated later. Incidental sharps and flats are written just before a tone, on the exact same tone position (but have no ledger line) and are valid for the tone immediately following, as well as for all identical tones in that bar only. The cancellation of any such an alteration is done by the natural sign ♮.

Summarizing:

- there exist 3 basic signs for alteration: ♯ sharp, ♭ flat and natural ♮;

- the sharp changes the pitch of a basic tone a semitone up;

- the flat changes the pitch of a basic tone a semitone down;

- the natural cancels a previous alteration sign in notation;

- sharps and flats can appear at the clef as a key signature (see section below).

EXERCISES 4

- Regularly practice reading tones and naming their enharmonic equivalences;

- Take care to evaluate the validity of accidentals in complex passages;

- Check sheet music at the Petrucci Music Library at imslp.org, e.g. an Inventio by Bach;

- To train and develop your speed of reading and naming, set a metronome to your reading tempo.

goto chapter 3 ► Building blocks of harmony – Scales

Oscar van Dillen ©2014-16